The Evidence Ledger

Turning Suspicion Into Evidence: How Law Enforcement Can Act on SARs

Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) are powerful triggers—but they’re not the full story.

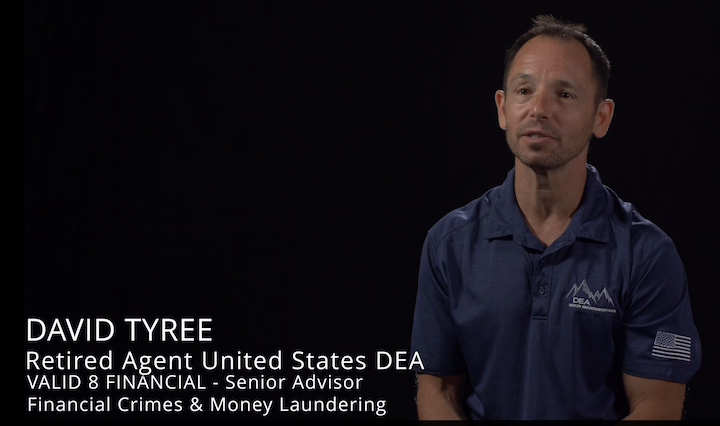

Filed by financial institutions, SARs are designed to alert regulators to suspicious behavior. But without the tools to transform that initial spark into actionable evidence, many cases fizzle out. David Tyree, a former federal DEA agent with hundreds of successful financial investigations under his belt, explains why SARs alone aren’t enough—and how Valid8 can help law enforcement close the gap.

Before we jump into the interview, let’s walk through the process of how criminals are caught through investigations that start with a SAR. There are a lot of nuances, but in general, it goes something like this:

- A bank or financial institution files a SAR.

- An investigator sees it in the FinCEN database and decides it’s worth looking into.

- They’ll reach out to the bank for supporting documentation—things like PDFs of bank statements, check images, spreadsheets, maybe even teller notes or video surveillance.

Then the real work begins.

Analyzing the transactions, looking for red flags like round-numbered cash deposits, unusual transfers, or activity that doesn’t align with the subject’s known income or behavior. If those financial clues line up with other intelligence—say, tips from informants, prior arrests, or surveillance—investigators start building a timeline that shows how the money moved and where it likely came from. That’s when they can start to link it to a crime.

Once the case is solid, it’s handed off to a prosecutor who decides whether the evidence is strong enough to press charges. If it is, and everything holds in court, that’s how an investigator goes from a suspicious transaction to an arrest and, hopefully, a conviction.

Q: SARs are meant to tip off law enforcement to potential crime—but what happens after a SAR gets filed?

David Tyree: Once filed, SARs go to FinCEN—the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. That’s the federal repository for all Bank Secrecy Act filings, including those from banks, credit unions, and even car dealerships if large amounts of cash are involved. But here’s the catch: banks are not required to notify law enforcement when they file. So it’s up to investigators to search FinCEN for relevant SARs.

Q: How can investigators effectively leverage SARs if they aren’t allowed to disclose them?

Tyree: Even when investigators find something that looks like actual criminal activity, most are hesitant to act on it because disclosing the existence of a SAR comes with both criminal and civil penalties designed to protect the person reporting the irregularity (ie, the “source”). What that means is, you can’t tell anyone—especially the subject of the investigation or their defense attorney—that a SAR exists or was the starting point for your inquiry. But to actually build a case, you need to get bank records, subpoena documents, maybe even go to court for a search or seizure warrant. And when you do that, you have to articulate why you’re asking for those things. That’s where it gets tricky. You’re walking a fine line between using the information in the SAR and not revealing the SAR itself. Most investigators aren’t trained on how to do that properly, so they either shy away from using SARs or don’t pursue the case at all. But there are legal, tested ways to build around it—you just have to know how to phrase it, how to leverage the intel without exposing the source.

Q: So how often do SARs actually lead to full-scale investigations?

Tyree: There’s no reliable stat. I’ve pursued over 500 cases using SAR-derived data—but that’s not the norm. Some agencies require investigators to check FinCEN, but they don’t always act on what they find. It really comes down to the individual investigator—their knowledge of how to leverage a SAR to build a case, their understanding of the process, and their tenacity.

Q: What makes one SAR lead worth pursuing over another?

Tyree: The quality of the narrative matters. Some banks go above and beyond in detailing what they’ve observed—especially in cases of suspected human or drug trafficking. A big red flag? An ongoing trend of round-numbered cash deposits from unknown sources. That doesn’t happen in the average family’s bank account. So when you see something like that, and you can’t explain the source of funds, it’s a lead worth exploring.

“Fingerprints used to be a novelty. Now they’re expected. Financial intelligence is the next fingerprint.”

Q: What's the difference between SAR intelligence and evidence that holds up in court?

Tyree: It’s simple. Investigators can use the data in a SAR—they just can’t disclose the existence of the SAR itself. They might write, “During my investigation, I discovered John Doe banks at XYZ.” Defense attorneys know subpoenas exist. You’re not hiding anything. But the SAR itself is treated like an informant—protected to prevent retaliation against the bank or teller who filed it.

Q: How can Valid8 help bridge that gap and convert SAR-based leads into usable case material?

Tyree: Valid8 creates what I call a “storyboard of money movement.” It’s visual. It’s demonstrative evidence. It turns all of those PDFs, statements, and spreadsheets of banking and accounting data into a single view of how money flows between accounts and entities. I’ve used it to brief agency leadership, pitch prosecutors, and explain complex cases to juries. Think of it like this: fingerprints used to be a novelty. Now they’re the status quo. Financial intelligence is the next fingerprint.

“Valid8 creates what I call a ‘storyboard of money movement.’”

Q: Can you give an example of a mistake you've seen when SARs were followed up on poorly?

Tyree: Definitely. In one case, a SAR flagged suspicious activity tied to a bank account linked to a guy who ended up getting pulled over with $60,000 in a backpack and a gun. Based on what we saw in the SAR and the circumstances of the traffic stop, we believed the cash was narcotics proceeds and seized it. But once the subject filed a claim to get the money back, we had to build a case proving it was criminal in origin. Investigators spent five weeks manually reviewing the bank records—only to miss a massive lead. When I looked through the data, I spotted a pattern of unusually high utility payments in Central California. That tipped off a local sheriff’s office, and they discovered one of the largest illegal marijuana grows in the region. But we missed the chance to seize additional assets. Why? Because we didn’t “open the aperture” wide enough, early enough—and we missed the bigger case.

Q: Do prosecutors underuse financial records because they’re hard to interpret?

Tyree: Yes. Juries understand car payments, rent, and everyday expenses. But they don’t always connect with abstract figures like the street value of 100 kilos of fentanyl. What resonates more is showing money moving in ways that don’t add up—like a cash-heavy restaurant worker making mortgage payments on multiple properties. That hits home. It’s all about how you tell the story.

“You take their drugs, they’ll find more. You take their money, you stop the machine.”

Q: How valuable is it to establish a "pattern of life" from transaction data—and does its usefulness vary by case?

Tyree: It’s critical. Whether it’s proving someone regularly travels cross-country when the person is on trial for drug trafficking or identifying spending behavior that contradicts a person’s alibi, transaction data fills in the blanks. It’s useful in everything from DUIs to homicide cases. If someone claims they didn’t deliver pills, but their Venmo says otherwise—that's the kind of evidence that can tip a case.

Q: What’s the typical turnaround time for building a financial case the traditional way—and where have you seen Valid8 make a difference?

Tyree: Traditional methods take months, sometimes years. One of my fastest cases still took six months—with me and two other agents working full time. Another took over two years. When I tested Valid8 with real case data—bank records and check images—it took 20 minutes to load and visualize. And just like that, the platform identified a million dollars I had missed. That’s not just speed. That’s case-changing intelligence.

Q: What factors increase the odds that a SAR actually leads to prosecution?

Tyree: Investigator tenacity is number one. IRS-CI, some DEA and FBI folks—they do it well. But it’s still the exception, not the rule. Everyone says “follow the money,” but too often it’s just lip service. If we actually follow the money—dig into the records, trace the flows—we can move up the food chain. You take their drugs, they’ll find more. You take their money, you stop the machine.

Q: Can you share a case that succeeded because of how well the financial intelligence was presented?

Tyree: One of my biggest cases started with a guy buying a car with cash—he had no credit, and he worked at a fast-food restaurant. That’s a red flag. We ultimately uncovered $8 million in suspicious movement tied to trade-based money laundering through restaurants in Colorado and Wyoming. It took over two years and led to the forfeiture of $1.8 million. Had I used Valid8, we could’ve built the case faster—and likely recovered even more.

The Bottom Line

SARs are the start—not the story. As financial crime grows more sophisticated, law enforcement needs the tools to keep up. Valid8’s platform doesn’t replace the investigator—it equips them to go further, faster, and with a higher chance of turning suspicion into prosecution. Want to learn more about how Valid8 can help improve the outcomes of your investigations? Contact us today.